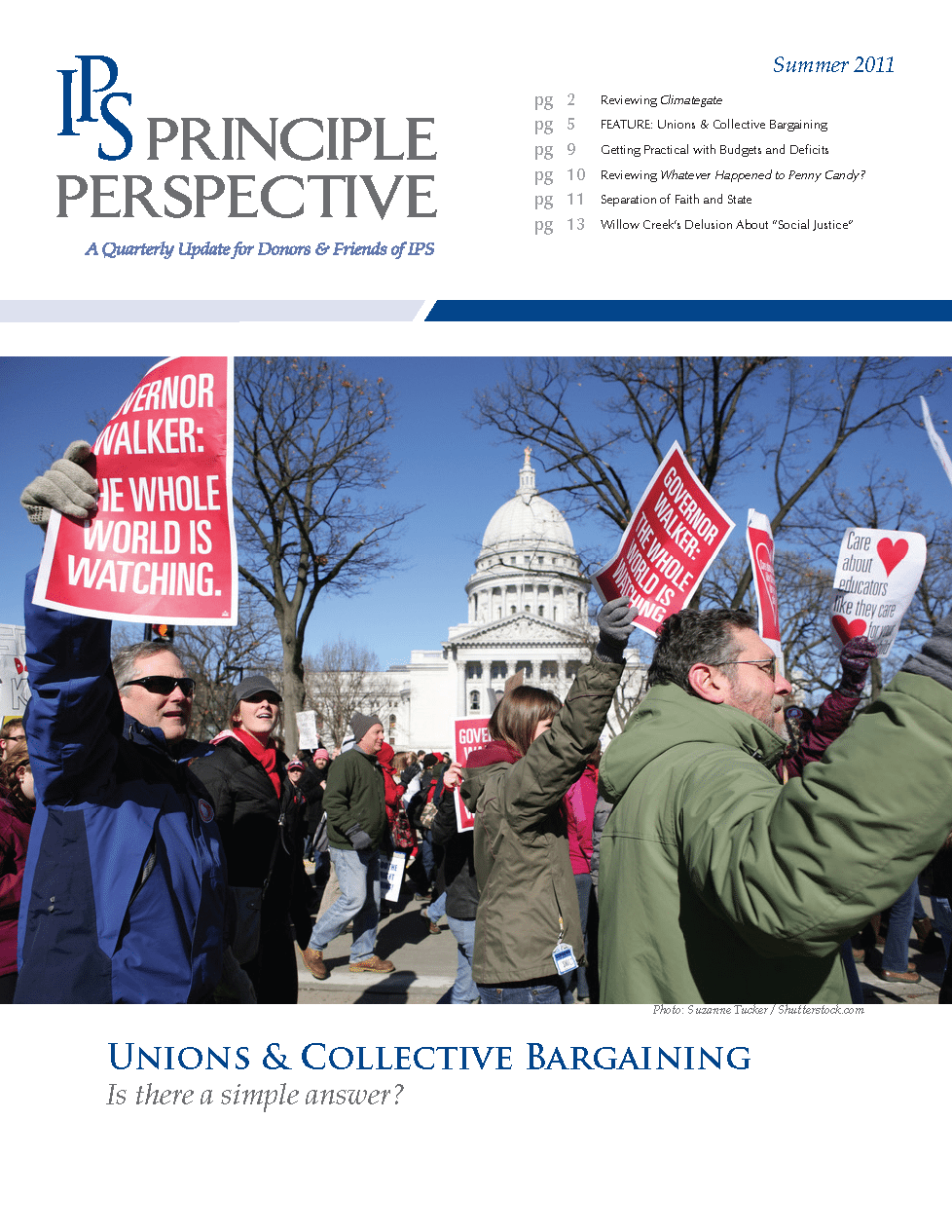

Unions & Collective Bargaining: Is There a Simple Answer?

An individual walks into a place of business seeking employment. The owner of the business and the job seeker interview each other, and both decide that an employment relationship may be to the benefit of each. They enter into negotiations over compensation and arrive at a mutual agreement on services to be performed and the pay rate.

Assuming that the work to be performed is ethical and legal, is there any reason why these two parties should not be allowed to pursue this employment agreement? You might be surprised to find out that federal laws in America limit this freedom.

There are frequent debates in America and throughout the world about the role of labor unions. This debate is typically framed as having two sides: those who are pro-union, and those who are anti-union. As is often the case with political issues in modern America, the controversies surrounding this issue are miscast. The real issue is not whether one is in favor of, or opposed to, unions. The real debate should be about our government policy toward voluntary contracts.

One of the functions of labor unions is to engage in collective bargaining—a process in which hiring and compensation are not decided individually, but collectively. There is nothing inherently wrong with collective bargaining, unions, or even a unionized labor force, as long as these union agreements are voluntary on the part of all parties. The problem is that current federal laws compel employers and employees to engage in contracts involuntarily. In a 1997 Mackinac Center article, Robert P. Hunter provides this overview:

When a union is selected to represent employees in an “appropriate” unit of workers, the union alone has the legal authority to speak for all employees, including those who neither voted for nor joined the labor organization. No other union, individual or representative may negotiate terms and conditions of employment, and the individual employee is effectively deprived of the opportunity to represent his or her own interests. This is known as the doctrine of exclusivity which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld in a 1944 case, J.I. Case v NLRB.

These limitations on both employee and employer are the result of a series of laws passed by our legislators over many decades. These laws have created and defined a small dictionary of specialized terms that describe the various ways in which lawmakers desire to reshape the workplace. Terms like “closed shop”, “union shop”, “agency shop”, and “exclusivity” are just a few of the special arrangements created by government and imposed on Americans by the force of law.

Read our entire in depth analysis by clicking the link below:

You will have access to the feature article in addition to topical articles

View Full Issue